In drawing classes at Bezalel, Doron Livneh likened the drawing to the act of telling a dream. We can expand the world of dreamers into reality. What is reality and the discourse that constitutes it, if not a more or less universal hallucination, cut off by death with a slash? Or, as Emmanuel Levinas poignantly puts it: "Death is always a scandal."

Scandal is present from the beginning of a person's life; it is his most intimate loneliness. It is embedded in the roots of his gaze and is revealed even more in the gaze of the photographer. The camera's aperture echoes the hole at the heart of being; the hole in the eye of the beholder himself. What has been lost even before it began.

Flipping through a family album can be a painful thing. There had been innocence there, faith, eternity, and there was a hole.

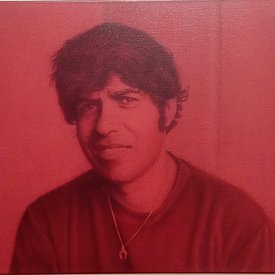

My act of painting after the photos seeks to reveal what persists in its wild existence before and after the photography takes place; to create a kind of encounter between the radiance of the subject's beauty in painters like Vermeer and Rembrandt and the mechanical, flattening, and chilling reproduction from the school of, Andy Warhol for example.

It is rare for family photos to be interesting to anyone outside the family. So yes, there is the family story, and here it is in brief:

My mother's parents, born in Eastern Europe, managed to escape the Nazis during the war and reached Palestine's shores on the immigrant ship 'Shaar Yashuv.' The British deported them to the refugee camps in Cyprus, where my mother was born. In 1949, after the establishment of the State of Israel, they immigrated there and settled in Kibbutz Kfar Blum. My father came from Iraq in the 1950s when he was ten. At the age of 24, he arrived at Kibbutz Kfar Blum - an Iraqi street cat who married the kibbutz's most beautiful girl, to the displeasure of her parents. My father's parents died before I was born, as did my mother's father. In the paintings, my father, mother, grandfather, and maternal grandmother appear at different ages.

The story can, of course, be expanded to include myths of psychoanalysis and personal and historical traumas that intersected and were etched into the soul, but the idiosyncrasy into which things are knotted exceeds, in my opinion, what can be said, what passes implicitly in glances and silences: Grandfather's silence, the silence of Mother vis-a-vis Grandmother; Grandmother, who, like my father, loved to talk, but in her late years suddenly stopped, choosing to remain silent with a kind of defiant stubbornness.

Some say that something in a person's gaze persists throughout his life: a singular note, like the soul's fingerprint. It stretches and gets tangled in the lives of others, embedding in them. It colors them and becomes colored by them. It is a real mystery. It may be painted violet or green. I relate to the green more (after all, it is the color of the kibbutz); not so much the violet.

That was what pushed me to paint. To try to hold on to those fingerprints, to extend my time with them.

"Each man kills the thing he loves," said Oscar Wilde. I did not wish to lose those I had loved. To have them fall out of an airplane in the middle of the night, and drop forever out of recognition out of reach.